Experts have raised concerns about the ethical implications of healthcare data storage and data security practices for years, and AI is taking up a larger share of that conversation every day. Current laws aren’t enough to protect an individual’s health data. In fact, a shocking study from the University of California Berkeley says that advances in artificial intelligence have rendered the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) obsolete, and this was before the COVID-19 pandemic. The truth is that healthcare data is incredibly valuable for AI companies, and many of them don’t seem to mind breaking a few privacy and ethical norms, and COVID-19 has only exacerbated the problem.

Consumer health data goes way beyond demographics

Healthcare providers, insurance agencies, biopharma companies and other stakeholders don’t just store typical consumer data (demographics, preferences, and the like). A typical patient’s healthcare file adds data on symptoms, treatments, and other health concerns.

AI in healthcare focuses on analyzing consumer health data to improve outcomes by suggesting diagnoses, reading medical device images, accelerating medical research and development, and more.

In this article, we’ll explore a few alarming ways AI solutions in healthcare are using consumer health data and how things have changed during the pandemic. As you read, consider this question:

How can we balance the potential for positive health outcomes with concerns over health data privacy, ethics, and human rights?

The largest social media platform uses AI to store and act on users’ mental health data with no legal safeguards in place

Healthcare privacy regulations in place from HIPAA don’t even begin to cover tech companies. HIPAA only protects patient health data when it comes from organizations that provide healthcare services, such as insurance companies and hospitals.

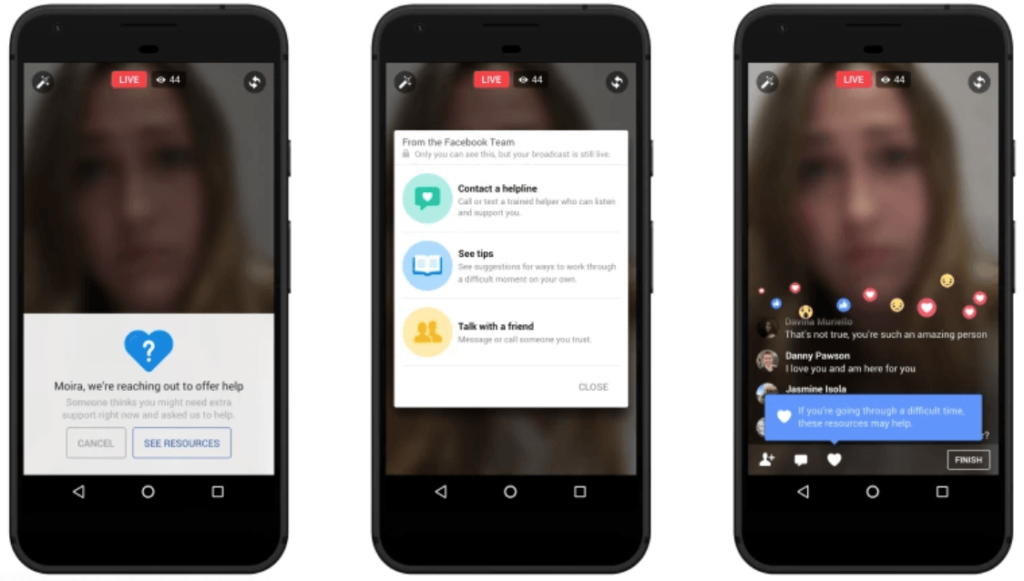

The upshot of this was demonstrated in late 2017 when Facebook rolled out a “suicide detection algorithm” in an effort to promote suicide awareness and prevention. The system uses AI to gather data from your posts and then predict your mental state and propensity to commit suicide.

The Facebook suicide algorithm also happens to be outside the jurisdiction of HIPAA.

Of course, this is ostensibly a positive use case for AI in healthcare. But benevolent intent aside, the fact remains that Facebook is gathering and storing your mental health data. And they’re doing it without your consent.

Also, few people really know what they do with the data they gather, beyond their stated purpose.

“In principle, you could imagine Facebook gathering step data from the app on your smartphone, then buying health care data from another company and matching the two,” says Anil Aswani, lead engineer on UC Berkeley’s privacy study.

“Now they would have health care data that’s matched to names, and they could either start selling advertising based on that or they could sell the data to others.” (Emphasis ours)

Genetics testing companies are selling customer data to pharma and biotech firms

HIPAA also fails to regulate genetics testing companies like Ancestry and 23andMe. These companies, which analyze your DNA to give you information about your health, traits and ancestry, don’t legally count as a healthcare service. And so, HIPAA rules don’t apply.

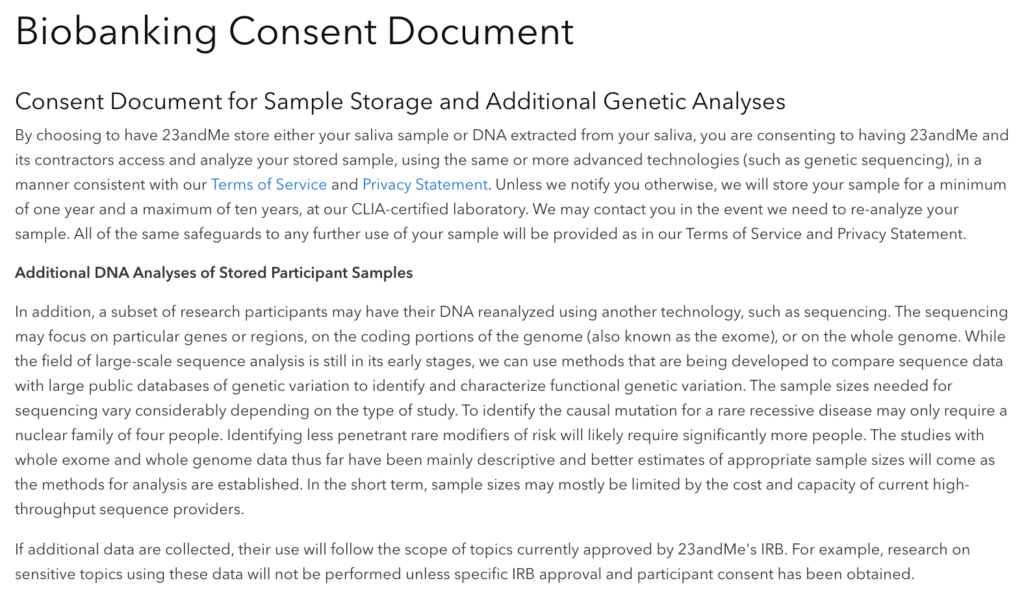

What’s more, 23andMe don’t exactly help. Their “Biobanking Consent Document” obfuscates exactly what DNA information the company can keep and how they can use it.

“By choosing to have 23andMe store either your saliva sample of DNA extracted from your saliva, you are consenting to having 23andMe and its contractors access and analyze your stored sample, using the same or more advanced technologies.”

23andMe also obfuscates how long they can hold onto your genetic data. “Unless we notify you otherwise,” they say, they can store your DNA for up to 10 years.

And don’t forget: These companies can and do legally sell their customers’ genetic data to pharmaceutical and biotechnology firms.

In fact, just last year 23andMe and Spanish pharma company Almirall signed an agreement to license a drug that treats autoimmune diseases — a drug that was developed using the personal genetic data of 23andMe’s millions of customers. And that followed a blockbuster agreement with pharma giant GlaxoSmithKline, which signed a 4-year, $300 million deal that allows GSK to access and analyze 23andMe’s stockpiles of their customers’ genetic data.

The stated goal of the partnership is “to gather insights and discover novel drug targets driving disease progression and develop therapies for serious unmet medical needs based on those discoveries.”

But would you say you really gave 23andMe informed permission to sell your genetic data? And how else could your DNA information be used?

Insurance companies could use genetics data to bias selection, pricing and more

Genetics testing companies don’t just tell you about your ancestry. They can also provide valuable information about your genetic predisposition to certain health risks. In fact, in 2017 23andMe received regulatory approval to analyze their customers’ genetic information for risk of 10 diseases, including celiac, late-onset Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

On the one hand, this is great for customers who can use this information to take preventative action or plan for the future. On the other hand, insurance underwriting experts are raising flags. They warn that, among other uses, insurance companies could use this predictive genetic testing to bias selection processes and charge higher premiums.

What’s more, due to higher statistical prevalence of certain diseases among certain demographics, there is a huge risk that incorrectly-trained insurance algorithms will demonstrate overtly racist and sexist behavior if left to their own devices.

Related Article: Bias in AI and Machine Learning

Thankfully, consumers do already enjoy some protections from these nightmare scenarios. In the US, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Acts (GINA) protects individuals from genetic discrimination in employment and health insurance.

However, these protections don’t cover every situation. For one, GINA does not apply when an employer has fewer than 15 employees. It also doesn’t cover military service people or veterans treated by the Veterans Health Administration.

Worst of all, GINA only protects consumers from genetic discrimination by health insurance companies. Life insurance, long-term care and disability insurance still don’t have their own consumer protection regulations.

The Office for Civil Rights has relaxed certain privacy rules during the pandemic

Even with these glaring holes in the regulatory environment in health data in the U.S., the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has actually further relaxed enforcement of certain privacy rules covered under HIPAA, as allowed under the Public Health Emergency (PHE) announced in January of last year.

Following are some of the areas that OCR and HHS relaxed during the pandemic:

- In March 2020, OCR announced that it would “waive potential penalties for HIPAA violations against health care providers that serve patients through everyday communications technologies during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. This exercise of discretion applies to widely available communications apps, such as FaceTime or Skype, when used in good faith for any telehealth treatment or diagnostic purpose, regardless of whether the telehealth service is directly related to COVID-19.

- In April 2020, OCR announced it would waive penalties for violations of certain provisions of the HIPAA Privacy Rule against health care providers or their business associates for the good faith uses and disclosures of PHI by business associates for public health and health oversight activities during the COVID-19 emergency.

- And in January 2021, the OCR announced that it would “not impose penalties for noncompliance with regulatory requirements under the HIPAA Rules against covered health care providers or their business associates in connection with the good faith use of online or web-based scheduling applications for the scheduling of individual appointments for COVID-19 vaccinations during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency.”

While all of these moves were made to expedite and improve care during the pandemic, the further relaxing of an already weak and outdated regulatory environment should be of concern to data privacy advocates and consumers alike.

To safeguard consumer health data, the US should learn from the EU

Clearly, HIPAA’s consumer health data privacy protections fall far short. What can we do? How can we safeguard individuals, while leaving tech companies free to build innovative solutions for AI in healthcare?

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a start. GDPR harmonizes data privacy laws across Europe, protects EU citizens and reshapes the way organizations in the region approach data privacy.![[ML black box.png]](https://www.lexalytics.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/03-300x287.png)

In fact, GDPR mandates that organizations must have informed user consent before they collect sensitive information. Perhaps not coincidentally, Facebook announced that their “suicide algorithm” isn’t coming to the EU – though of course they didn’t explicitly mention GDPR.

Note that policies like the GDPR don’t make a distinction between “tech companies” and “organizations that provide health services”. Under the law, all organizations must obtain informed, explicit consent to collect user data. This comprehensive policy approach both creates effective consumer protections and enforces them with heavy fines and penalties.

But it’s not all good news on the European front

In another case of AI healthcare controversy in Europe, the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) found that an agreement between Google’s DeepMind and the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust breached UK law.

As part of their partnership, the Royal Free Trust (RFT) provided massive quantities of patient data to Google. DeepMind’s AI then ingested and analyzed that data, with the goal of improving patient care by helping doctors to read medical imaging results and suggesting diagnoses.

Unfortunately, the ICO found that the Royal Free Trust failed to adequately inform patients that their data would be used as part of certain tests. “Patients would not have reasonably expected their information to have been used in this way, said Elizabeth Denham, Information Commissioner, “and the Trust could and should have been far more transparent with patients as to what was happening.”

Among other requests, the ICO asked the Royal Free Trust to commission a third-party audit of their practices. This audit, completed in 2018, concluded that RFT’s program was lawful and complied with data protection laws. But it should be noted that the auditors were engaged by RFT themselves. And lawyers are already questioning why the ICO didn’t give RFT a more serious penalty.

More recently, in the Netherlands, two health ministry workers were arrested for a hack that took place in December 2020 of COVID-19 patient data that was later sold online. While the number of patients impacted wasn’t disclosed, the event underscores the importance of constant vigilance for such attacks and that even in a heavily regulated environment, breaches are still possible.

With AI in healthcare, we must consider the human element

Of course, there isn’t a single solution to our concerns over AI in healthcare. But it’s important to raise the question and discuss past and potential outcomes.

Lexalytics, an InMoment company, CEO Jeff Catlin has seen many AI systems crash and burn over the years. He argues that although AI is an incredible tool, it’s still just a tool. “AI can’t be expected to do it all,” he says. “It can’t take the challenging problems out of our hands for us. It can’t solve our ethical dilemmas or moral conundrums.”

Indeed, the humans behind that tool must take ownership. We are responsible for how we use them. And we must make sure that privacy policies, and ethical standards in general, keep pace.

And we can at least make a few general recommendations.

First, tech companies must be required to educate users on exactly how their data will be used. Then, users must have the option to decline consent.

Second, technology companies themselves need to step up and take the initiative to build appropriate technical safeguards into their AI healthcare solutions. Where they fail, we must hold them accountable.

Third, governments must implement up-to-date legal frameworks surrounding healthcare data. AI and healthcare companies big and small have proven that they can’t be trusted to always self-regulate here.

Once we’ve cleared these ethical and moral hurdles, AI solutions for healthcare will deliver invaluable medical breakthroughs and quality-of-life improvements. But we can’t forget the humans whose data those AIs will learn from.